Power Through Your To-Do List with Time Blocking

Published:

Before starting grad school, I had a job (really, four successive jobs) as a writer at an advertising agency. For the purposes of this post, the important context to know is that advertising agencies are incredibly bifurcated. The account people manage the business side of things, interacting with clients, building relationships, and drumming up business. The creatives—writers, artists, graphic designers, web developers—create the advertising product.1

All of these advertising agencies (extrapolating from the four at which I’ve previously worked) have the same workflow. First, the account people meet with the client to develop an advertising strategy (e.g., X units of billboards, Y units of TV commercials, Z units of Instagram posts) that will help said client achieve their business goals. Then, the account people hand this plan over to the creative team(s) who create an overarching concept or theme (think “Jake from State Farm” or “The Geico Gecko”). They use this concept to spin out the art and writing that goes on those Xs, Ys, and Zs. Finally, the account team takes this package, convinces the client (sometimes with the help of one or two creatives) that it is a good idea that will increase revenue, and they ensure the images on the computer actually end up on a highway or whatever.

I bring all of this up because, in my limited experience, few industries operate with such a clear distinction between managers and makers. Account people are the managers; creatives are the makers.2

The relevant difference between these two pure types is, as Paul Graham points out, how they think about time. Managers look at the world and see one-hour intervals. From 8-9, meeting A. From 9-10, meeting B. From 10-11, catch up on email. Makers look at the world and see large blocks of time in which they can do deep work. From 8-12, write billboard headlines. From 1-3, write website copy.

Makers and Managers

Neither of these approaches to time is good or bad or “correct.” The issue, though, is what happens when they come together in the same place of business.

In my extended advertising metaphor (I swear I will stop complaining about jobs of days-gone-by and get to grad school soon), the problem was when account people would schedule a meeting at 10am. For makers, as Graham writes,

“..one meeting can sometimes affect a whole day. A meeting commonly blows at least half a day, by breaking up a morning or afternoon. But in addition there’s sometimes a cascading effect. If I know the afternoon is going to be broken up, I’m slightly less likely to start something ambitious in the morning. I know this may sound oversensitive, but if you’re a maker, think of your own case. Don’t your spirits rise at the thought of having an entire day free to work, with no appointments at all?”

It does sound a little dramatic, but that doesn’t make it less true. A meeting at 10 (rather than 9 or 11) would be an excuse to slack off for the entire morning. There wasn’t any time to get anything done! Even though two hours is two hours, two back-to-back one-hour blocks allows for an entirely different kind of work than two blocks split by a meeting.

Academics—like most professionals—are neither pure makers nor pure managers. They fall somewhere in the middle of the distribution. They are makers when they explore a new dataset, connect disparate research literatures, write articles, and design courses. They are managers when they set deadlines for exams and papers, manage research teams, and sit on hiring committees.

But at the end of the day (…err, the end of the five or six years?), what the job market values is the maker work. The publications, grants, and course designs. These things require focus, creativity, and—importantly—long stretches of uninterrupted time in which to focus and be creative. Even first-year grad students, consumed by coursework, need long blocks on time in which to complete their reading and problem sets.

Time Blocking

If you believe, as I do, that you need long blocks of time to do your best academic work (but, perhaps, you never have those long blocks of time?), then I would recommend a productivity system called Time Blocking.3 The method is, essentially, what it says on the tin. You just…block out your time.

But, I am being a bit cheeky. “Simply” blocking out your time is not so simple in practice.

A Different Mindset

Most of us work in reaction mode.

We keep a running list of to-dos, and when we sit down at our desk, we look at this list. We choose a task that feels doable—let’s say, writing the introduction to an article—and we start working. Then, an email comes in from our advisor. Oh, it’s just a small thing.

Well…it seemed like a small thing at first…

…

…Now, after an hour of work on what was supposed to take 15 minutes, it’s done. Send it off. Back to writing that intro. 15 minutes goes by. Oh, another email. The advisor has a follow up question. That should just take five minutes, right? And, what’s this? A student in the class you TA wants to meet.

You can see where this going.

Time blocking asks that you be more proactive about how you use your time. Instead of waking up, looking at your to do list, and choosing whatever feels easiest or most pressing, you assign your future-self jobs and block out the time in which you’ll do them the day before. Then, when that time comes, you do those jobs. Importantly, you don’t look at email. You don’t react to alleged “quick” requests. You don’t check Twitter. You just do the assigned task. When the time block runs out, you look at your calendar and do the next thing.

The benefits here should be clear. First, you don’t waste any time in the morning deciding what to work. Second, you don’t avoid working on difficult tasks; you have no choice but to do what your past-self assigned. Third, you actually do the deep work because you’ve intentionally made time for it.

Implementation

Now, how does one go about shifting from reactive mode to proactive time blocking? Here is how I actually implement this system:

Although unconventional, the first day of my week is Wednesday (not Sunday or Monday). That is the day I meet with my advisor to get feedback on my solo projects, discuss the projects we’re working on together, and plan ahead. I block out time (45 minutes) immediately following that meeting for a weekly review. I’ll save the specific details for another day, but the gist is that during this time, I review my to do list and begin assigning tasks to blocks.

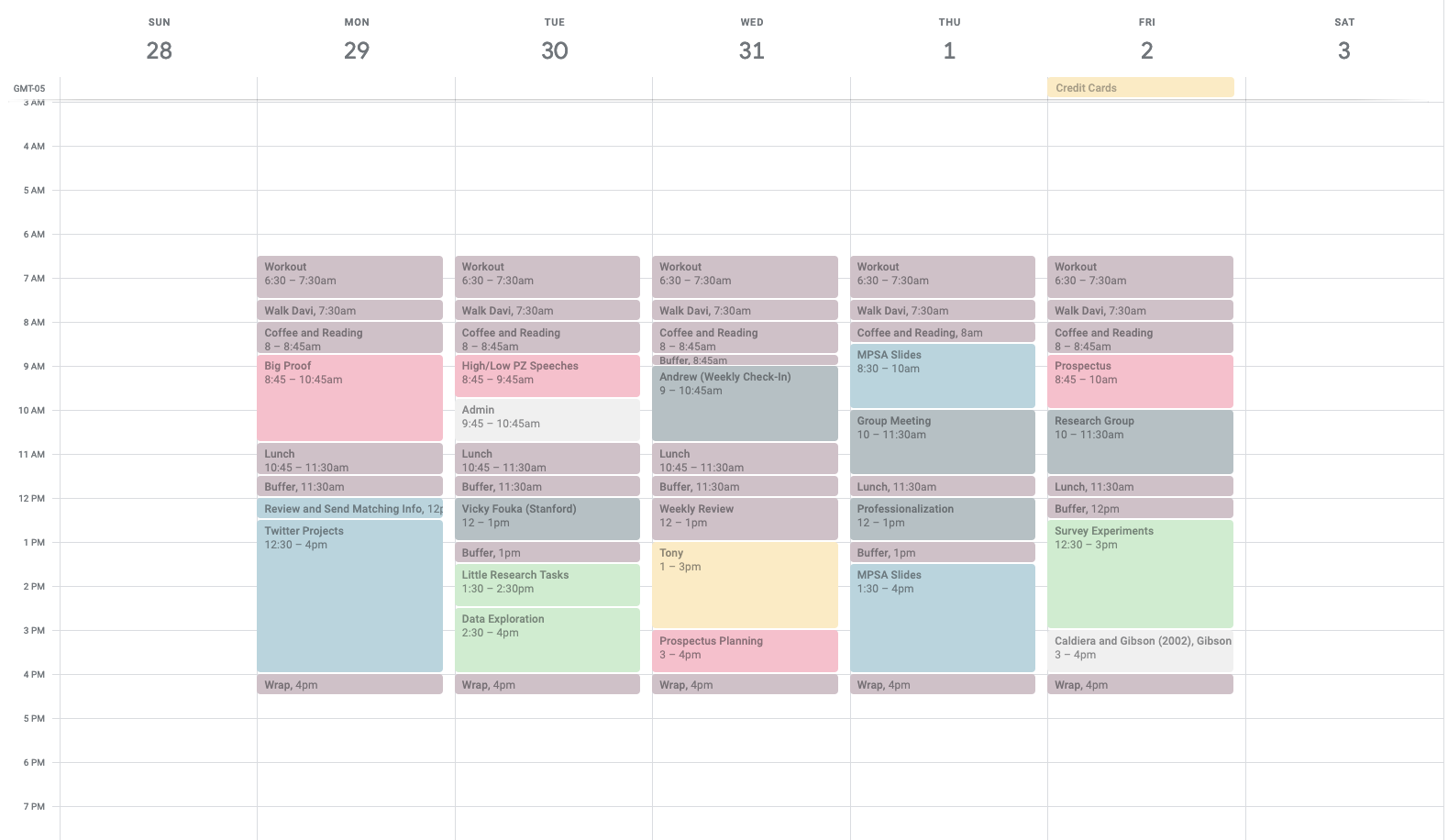

I start with a “blank” calendar, which already includes blocks for non-negotiables: working out, reading news, lunch, seminars and meetings, etc.

Note that “coffee and reading” is not academic reading, but rather, reading the news and catching up on blogs. Time blocking does not mean that I work like an unfeeling automation from 8AM to 5PM. I schedule regular time to read the news, check social media, and take walks. Scheduling these breaks wards off the temptation to tab over to Twitter during a work block and also ensures that I actually take them.

During this review, I look at the open space and map out what I think my future-self should work on and when. Often, I am a better writer in the morning, so that’s when I assign writing tasks. I save the afternoon for coding, reading, or admin.

Of course, this schedule is tentative. Things can and will come up over the course of the week and I’ll want to bump things up or down. That’s why I have a short block called “wrap” at the end of each day. That’s when I look ahead to the next day and make any changes based on new priorities or tasks I did not finish in the alloted time.

Troubleshooting

Some points you may want to raise…

What if I do not finish a task in the assigned block?

That is fine. Estimating your time is hard, and I am not so good at it either. My general advice would be that, when the assigned block ends, stop working on Thing X and move on to previously-scheduled Thing Y. At the end of the day, you can adjust your schedule for the coming days and add another block for Thing X.

Why? Suppose you keep working on Thing X until you finish it. Let’s say it takes an hour. That eats up half of the next block, which you were supposed to spend on Thing Y. Now what do you work on? You could start Thing Y, but you just have a short block. Do you do Thing Z, which won’t take as much time? Now you’re back to where you were before you started time blocking.

I also find that the longer I keep pushing on Thing X, the longer it takes to finish. It’s better to step away and come back to it with a clearer head and fresh eyes. Of course, these are just general guidelines. If the thing is due at the end of the day, then you probably have to finish it.

What if I have a day with weirdly scheduled meetings and no long blocks of time for deep work?

I hate those days, but they happen. And that’s why it’s good to look at all your tasks and make a provisional schedule at the beginning of the week (knowing it will change). If Wednesdays and Fridays are good for deep work, put your difficult writing and coding there. If Thursdays are weird, full of meetings and awkward hour-long blocks, then save those for interruptable tasks like reading articles you’ve been putting off, making tables and figures, or proofreading. Make the point of not scheduling those things on Wednesdays and Fridays when you have longer time blocks.

What if I cannot block my time because my advisor expects that I drop everything and respond to their every whim?

I feel for you. That is no way to work. And I agree, time blocking might not be possible in that case. The power of time blocking comes from working on one thing for a long period of time without interruptions or multitasking. My suggestion—although potentially uncomfortable and difficult—would be to talk to your advisor. Explain that you work best when you can concentrate on one thing for a period of time without interruption (that’s just science). Assuage them by promising that you will respond to their requests the day they are sent, but not the minute or hour. Then, when mapping out your week, schedule blocks for “advisor response time.” You’re allowed to be reactive, but the point is that you set aside a specific time for reaction rather than bouncing back and forth from thing to thing.

Even if your advisor doesn’t expect you to drop everything and respond to their requests, it might still be a good idea to proactively schedule “reactive time” or “flex time.” Best case scenario, nothing comes up, and you can use that block however you want—even if that means checking social media.

If you have other questions, feel free to email me and I can respond to you/update this post.

–

Although I have always tried to set aside time for deep work, this year with the pandemic, I’ve gotten more intentional about time blocking. It probably won’t work for everyone, but if it sounds appealing, try it out for a month. It will be difficult at first, but stick with it. I bet it will pay off.

Maybe you already know this from watching Mad Men? I’ve only seen the pilot. ↩

The relationship between these two groups is often toxic. The creatives believe they are very special and talented, but also disrespected and put upon. The account people think the creatives are divas who just mess around all day and complain. Meanwhile, the account people think, we actually go out and find money to subsidize the creatives’ goofing off. As a former creative myself, it is incumbent on me to say that the creatives are very special, talented, put upon, and disrespected (haha). But since we are deep in the footnotes, I will also acknowledge that creatives are usually grumpy and introverted. They would hate to do the work of the account people—like talking to people or thinking about money. ↩

If you want to get serious about time blocking, the linked article is a great resource. ↩