Just Treat It Like a 9 to 5 Job and Everything Else Will (Probably) Follow

Published:

How do you get a tenure track job?

How do you get tenure?

How do you get to full professor?

The answer is obvious: write. And publish.

How do you write and publish?

That answer is also obvious: sit down at your computer, open a blank document, and start typing.

Even if the answer is obvious, doing it is not. For starters, “typing” won’t cut it.1 You need to come up with good ideas, read the literature, collect and analyze data, write a persuasive argument. The list goes on.

These are difficult tasks. And there is no formula for doing these tasks consistently and at a high level.

For that reason, I (and many others) write blogs like this with advice on how to have more ideas, how to read more efficiently, and how to organize your time effectively. Or, sometimes, just the opposite. How to take breaks, avoid burnout, and make time for yourself.2

I (and many others) read blogs like this because we are searching for the “one weird trick” that is magically going to destroy distractions, give us writing superpowers, and finally help us finish that article we’ve been avoiding—all while having time to pursue our hobbies, maintain important relationships, and live life.

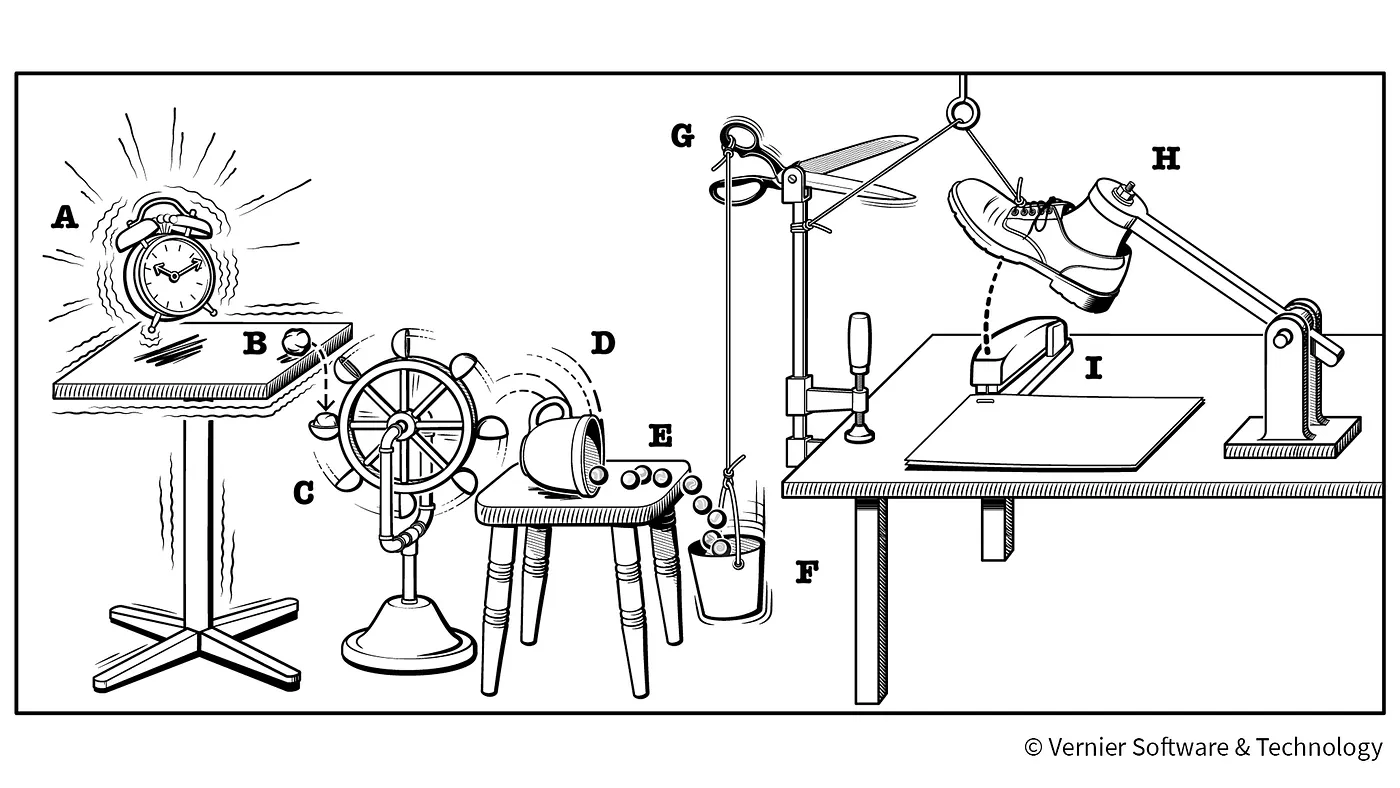

After years of being one of those blog readers, I’ve stumbled upon many of these “one weird tricks,” like:

- Time blocking.

- Eating the frog.

- The pomodoro method.

- Creating a writing group.

- Some sort of Rube Goldberg productivity system involving this cool new app that will definitely, totally work this time and that you definitely, totally won’t abandon after you spend all of today and most of tomorrow setting it up (all while avoiding your actual work).

Now, I don’t want to sit here and say these “one weird tricks” don’t work. I have used, and still use, many of them. But consider how many “one weird tricks” you can find on the internet. And how you’re still looking for the “one weird trick” to rule them all. And how you’re reading this article right now. The simple fact that we’re all still searching suggests that none of these “one weird tricks” actually solve the core problem. They never help us maintain the work-life balance we’re seeking.

As I, myself, was reading about the latest “one weird trick” something hit me. What if all of these “one weird tricks” are downstream of a “one weird trick” that actually works. A “one weird trick” so boring, so unappealing, so un-sexy, that no one ever stopped to think that it might be a “one weird trick” at all.

Until now. Until I was brave enough to do it!

So what is the secret to productivity?

Pretend you work a 9-5 job.

Before academia, I worked a 9-5

For five years between undergrad and grad school, I worked in advertising. I was a writer. I wrote scripts for TV and radio commercials, copy for websites, and headlines on billboards. In the beginning, advertising was a fun, creative, and challenging career. But there was one problem: every weekday, Monday through Friday, I had to wake up early, go to an office, and sit there from 9am to 5pm.

Looking back, the job wasn’t so different from what we do as academics. I had to come up with novel and creative ideas. I had to write those ideas down. I had to present my work to internal and external stakeholders who would review it and give me feedback. I had to revise my work based on that feedback. I had to re-present that work. Often, I had to do all of this while working with a small team of 1-3 other people.

But there were a few key differences. Some are particularly relevant here: if I did not sit down at my desk and write, I would get in trouble. If I did not make the revisions on time, I would get in trouble. If it was summer and it was a really nice day and things were slow and I decided I didn’t feel like working and I went to the park instead, I would get in trouble. If it was really busy and I was juggling a lot of projects and the emails were piling up and the election was, like, five weeks away and I really just couldn’t and I took the day off—even then—I would get in trouble!

So what did I do?

Obviously, I quit and became an academic.

But for five years…I went and sat down at my desk from 9-5, Monday through Friday. And I wrote. Because I don’t like getting in trouble.

The Autonomy Tax

Now, fortunately, I make my own decisions. I get to choose what to write and when to write it—or even, whether to write at all. And guess what, I don’t ever get in trouble!

But this autonomy, this “not getting in trouble,” it’s not quite what it seems.

With autonomy comes extreme responsibility.

Yes, it’s awesome that no one will tell you what to work on, when to work, where to work, or when to turn in your work. But there are some downsides too. Like…no one will tell you what to work on, when to work, where to work, or when to turn in your work. You have to tell yourself that. And then you have to follow through.

But following through is hard, because writing is hard. And doing basically anything else is easier.

The autonomy tax is this: when you wake up in the morning, you have options. You could clean your data, or compile code, or write your introduction, or read some articles, or start a new project. Or, you could fold your laundry, or clean your oven, or go to the beach, or call your mom, or go to the DMV, or lie on the floor and stare at the ceiling. I know what I would choose. Because writing is hard.

Every time you have to engage in this kind of decision-making, you are taxing a finite resource: your cognitive capacity. And this mental energy is exactly what you should be using to think about your theoretical arguments or data sources or analytical approaches—not whether you should or shouldn’t be working in the first place.

The “one weird trick” to rule them all

Thinking back on my time in advertising, one (not so) strange fact is that I never called my mom or folded my laundry in the middle of the day. Not because my preferences changed. But because if I wasn’t at my desk writing, I would get in trouble.

If you are struggling to get work done and “one weird tricks” aren’t working, it might be because you’re viewing your work as a thing you could do rather than the thing you should do. Because, after all, you won’t get in trouble if you fold your laundry or call your mom or even bake cookies. And you can always work tomorrow. You’ll be better rested. More inspired. Less stressed.

And if that is your mindset, no pomodoro method or time blocking or Rube Goldberg-ian system will help you. Because you won’t be at your desk to even apply them.

The “one weird trick” is this: cultivate a lifestyle where you don’t have to make these choices. Where you don’t think about folding laundry or calling your mom or baking cookies in the middle of the day. Where you don’t have to make these hard choices where writing is destined to lose. Where you wake up every weekday, Monday through Friday, and you sit at your desk and write. In short, simply take all of the freedom and flexibility afford by an academic job and set it on fire.

By removing the recurrent question of “should I work now,” and simply defaulting to 9 to 5, you can conserve your mental bandwidth for the thinking that actually matters.

What do you get in exchange for working 9-5? Freedom from 5-9.

Ok, I admit, it’s starting to sound a little toxic. I’ve mostly just lectured you about working 40 hours a week (which to be fair, I do believe will help you be more productive) without giving you anything in return.

But you do get something in return.

When I worked in advertising, it’s true, I couldn’t go to the beach at 2pm because I felt like it. But at 7pm, I can assure you, I was not thinking about my job. I never felt guilty for reading fiction, or playing video games, or hanging out with friends. There was never that feeling of “oh, I should be working right now.” There was no ambient and ever-present guilt. Work wasn’t my problem…at least until tomorrow at 9am. And at that point, I knew I would have eight dedicated hours to deal with it.

Many academics struggle with feelings of guilt, constantly questioning if they have done enough. If they can allow themselves to be “done” for the day. It’s easy to feel this way when you don’t set clear boundaries between work and play. When every minute is a choice between working or relaxing, of course you feel bad when you choose relaxation. You could have chosen work!

When you establish a consistent 9-5 routine though, you’re never faced with this choice. You simply look at the clock. If it’s between 9am and 5pm, you work. If it’s not, you don’t. You never have to feel bad about what you should be doing, because you’re already doing it!

How to work a 9-5 job.

Some people don’t know how to work a 9-5 job. So finally, we get to the practical advice from my wealth of experience. Here’s how you do it:

You wake up with enough time to do whatever it is you need to do in the morning (work out, eat breakfast, read the news, take your children to school, walk your dog, etc). At 9am, you sit down in front of your computer and start working. Take a short break to check social media or walk. Around noon, take 30 minutes for lunch. Then, sit back down at your computer. Maybe one or two more short breaks. At 5pm, close your laptop.

At 5:01, bake, watch TV, walk your dog, call your mom, go to the beach, go out to dinner, play video games. And don’t think about work! The world is your oyster.

Repeat, five days a week, fifty-two weeks a year—excluding major holidays, vacations, and sick days—until you get [an academic job, tenure, full professor, an APSA career achievement award].

Maybe you still have some questions…

Q: What should I do if I don’t feel like writing today?

A: Sit at your desk from 9am to 5pm and write.

Q: What if I am stressed about the election?

A: Sit at your desk from 9am to 5pm and write.

Q: What if I am tired?

A: Sit at your desk from 9am to 5pm and write.

Q: What should I actually do while I “sit at my desk from 9am to 5pm?”

A: Most importantly, “write.” Whether that is the actual text of a book or article. Code. Collect data. Mentor students. Prep courses. Teach courses. Read relevant literature. Answer emails (sparingly). Attend talks. Do service.

Academia is not just one thing. It’s a collection of different roles and responsibilities, all of which count as “work.” Different engagements, and interruptions that fragment your workday. This reality makes boundaries more essential—not less. Writing, teaching, mentoring, service, and administrative work all “count” and fall within these working hours.

When your lecture ends at 2, you return to your desk and analyze data or prepare another lecture or email a coauthor rather than disassociate on instagram for an hour and go home with some vague intention to “work tonight.” When you have odd breaks between committee and student meetings, you use that time to respond to emails or read an article rather than doom scroll.

Q: What if I need to go to the doctor or the DMV? What if I’m sick?

A: Just like people with actual 9-5 jobs, take time off to do necessary errands or take care of yourself. But don’t take advantage of your flexibility. Sick days and dental appointments are essential; going to Walmart to pick up supplies for your Halloween costume is not. If you’re not sure, ask yourself: what would one of your 9-5 friends say if you told them how you were spending your work day? Would they be jealous? If so, you probably shouldn’t be doing it!

Q: What if I can’t be creative on demand? What if I need inspiration to write—which may or may not come between 9-5?

A: The author Somerset Maugham once wrote:

“I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

While it’s true you might get a flash of insight at 11:56pm (it’s certainly happened to me), creative work often happens due to, not in spite of, constraints. By setting aside dedicated time to work, you’re training your brain to get into the right state of mind at the right time. And you’re making space to engage in creative work, rather than leaving it to chance. Boredom is the mother of creativity. You’re much more likely to come up with innovative solutions when you’re sitting at your desk with nothing else to do than you are baking in your kitchen and listening to a true crime podcast.

And what’s more—the work of academia is about much more than having a brilliant idea. It’s about translating that idea into an article with theory and evidence. It’s about writing lectures and teaching and mentoring students. It’s about performing service for the department and the discipline. These things do not require flashes of insight. They require time.

Do I literally have to work from 9am to 5pm? What if I work better [at night, in weird two hour chunks, for eighteen straight hours without a break]?

My main point is that you want to set dedicated blocks of uninterrupted time to work each week that are consistent and repeatable. You want to mentally categorize certain chunks of time as “working hours” so you never have to choose between work and play. Doing so eliminates the autonomy tax so that you can save mental energy for meaningful work.

Different people have different preferences and different working styles. The flexibility to work whenever you want is a huge draw of the career. And there is nothing innately magical about 9-5 (relative to, say, noon to 8pm). It’s not some sort of empirically validated period of maximum productivity. It’s just a socially constructed focal point that we have collectively decided is “work time.”

But focal points have their advantages as coordination mechanisms. Because most other people are working during this time, doing so yourself is the path of least resistance. Everyone else is working, so it’s easy to do what everyone else is doing. Your advisors and colleagues are most likely to be in the office during this time. They will be more responsive to emails. There’s less likelihood of a meeting being scheduled outside your usual working hours (e.g., at 9am if you work starting at 11am).

There are also fewer temptations that will pull you away from work. Most of your other friends (unless they’re also academics), aren’t going to text you at 2pm on a Wednesday to get dinner. There aren’t any concerts or comedy shows at 11am on a Thursday. No one hosts a Halloween party at 3pm on Monday. All of these things happen outside of the 9-5 window, and since you worked 9-5, you’re free to do those things when they come up. If, instead, you decide your working hours will be noon to 8pm, you will need incredible willpower to turn down your friend’s 6:30pm dinner invite. And if that is the schedule you set, you need to stick to it. Otherwise, you’re back to the world of too many choices.

I get what you’re saying, but how does sitting at my desk magically make me more productive and successful?

On it’s own, sitting at your desk solves nothing. But sitting at your desk gives you the time you need to solve something.

In my post on having more ideas, I write:

“Having good ideas is hard. But having bad ideas is easy.”

Having bad ideas takes time. The same applies to writing. The best way to write a good paper is to start by writing a bad paper. But again, even writing a bad paper is hard and takes time.

You typically don’t have bad ideas while you’re baking or listening to podcasts or doom scrolling. You have bad ideas when you’re sitting at your desk with nothing else to do and no escape until 5pm.

I thank Debora Villalvazo for helpful discussion and feedback on this post.