Six AI Applications Every Academic Should Try

Published:

Academics are not early adopters.

Sure, we have computers and e-books and email. But are we really that different from our medieval predecessors—reading and writing books, challenging one another’s evidentiary claims in the seminar room, sharing knowledge with students in large auditoriums? We tend to adopt technologies that make our lives easier (digital articles, statistical software) but resist that those that threaten the core elements of our job (recording lectures, online courses, Wikipedia).

So when it comes to AI, I understand why academics are resistant.

Yes, it can make our lives easier. But it’s also the one technology that most directly threatens our roles as knowledge producers and educators.

Maybe you’re rolling your eyes right now. How could AI possibly replace us? Perhaps you, like some of the scholars I’ve talked to, view AI with skepticism. You argue that these tools are ineffective. The applications are unnecessary. LLMs hallucinate fake sources. They write code that any undergraduate with an internet connection could produce. They consume a bottle of water just to draft a quick email to your department chair. What a waste of time.

Or maybe you’re shaking your head. Maybe you are like some academics who view AI with disgust. Perhaps you feel LLMs are plagiarism machines that devalue academic rigor. They rob us of our creativity and our patience for critical thinking. To take advantage of these tools is to admit that we, as researchers and educators, add no more value than an unthinking computer that can do matrix multiplication with words.

If you fall into one one of these camps, you are missing something important. While these criticisms are sometimes accurate, they also stem from a misunderstanding of how to use these tools, not from a limitation of the technology itself. And I get it. Unlike almost any other technological innovation, AI doesn’t come with an instruction manual. LLMs do not behave based on clear rules. The same input does not always yield the same output. And these tools are constantly evolving.

But that doesn’t mean the technology is useless.

As Professor Ethan Mollick wrote on X last year, the best way to understand what this technology is capable of, and how it can be of use to you, is to see what others are doing with it and to experiment yourself. That’s what I aim to do here.

After learning more about this technology, experimenting with these tools, and prepping a course on integrating AI into the research process, I have identified six different ways AI has benefited my research and teaching. These range from obvious insights to advanced applications, and they’re use cases you can experiment with today. As I’ll show, they complement rather than substitute for my core skills, and they have required me to think more carefully, not less.

Research

Debugging Code (Obvious)

Not too long ago, I was a fresh-faced graduate student trying to mutate() my first variable in R. I remember clicking through stackoverflow, puzzling over the differences between the correct solution and my busted code.

But those days are over. My own undergraduate and graduate students will miss out on this experience (just as I missed out on my senior colleagues’ trips to the mainframe to run their regressions). Now, I copy and paste my error messages into ChatGPT and get a perfectly tailored solution in seconds.

This is low effort, and often low reward. But low rewards compound. As a political scientist, my job isn’t to be the world’s most knowledgeable coder—it’s to publish impactful research. By quickly solving bugs, I can get back to what matters.

Synthesizing Bodies of Literature (Ambitious)

When ChatGPT first blew up in early 2023, I asked it about the major citations in my own research area. It failed miserably. Some of the authors were real, but the books and articles were completely fabricated. It was apparent that these models, while good at generating text, were not good at information retrieval. Which was frustrating. If only these models could identify and summarize actual sources, they would be especially useful in the early stages of project planning and literature sourcing.

With the advent of “deep research,” that’s changed. Using this feature, an LLM will “think” for ten or twenty minutes. It will search the web for answers. And when it finishes, you’ll have a high-level, 4,000 word report summarizing the literature. The actual literature.

Now, the point isn’t to have the LLM do the work for me. I don’t copy and paste the content into my Overleaf file. Rather, these deep research reports scaffold deeper investigation. Getting this rapid synthesis allows me to step back, orient myself, ask better questions, identify gaps, and figure out what to read next.

Getting Critical Feedback (Advanced)

If you think the seminar room is tough, try asking ChatGPT for feedback on your talk.

A few months ago, I was scheduled to give a 30 minute research talk to a non-specialist audience. Although I was excited about the opportunity, I was unsure if I had effectively blended academic rigor with approachable storytelling appropriate for this audience.

When I finished what I thought was a solid first draft, I recorded a practice run and shared it with ChatGPT. Two minutes later, it provided a 2,000 word review highlighting strengths, but also detailing structural issues, technical jargon, and recommendations for a smoother presentation. I was shocked. Not only because I consider myself a skilled presenter, but because many (maybe 60%?) of these suggestions were good. They were the kinds of things a colleague would have noted had I asked them for feedback.

What about the other 40%? Since it’s just you and me here, I’ll admit: they kind of sucked. Some of the feedback suggested I remove humorous asides. And worse, some of the suggestions seemed to hinge on revising slides that didn’t exist.

At this point, I know many people will roll their eyes. Why waste time with a tool that gives feedback on hallucinated slides? What a joke, right?

This is where critical thinking and flexibility are essential. Consider the last time you got a good journal review or that a colleague gave you feedback on a paper. What percentage of their suggestions were helpful? How many did you implement? I doubt you agreed with 100% of what they suggested, and yet, you still valued their input. Similarly, I trust myself to recognize good and bad feedback. AI doesn’t have to have a 100% success rate to be valuable or improve my work. An all-or-nothing approach helps no one.

Teaching

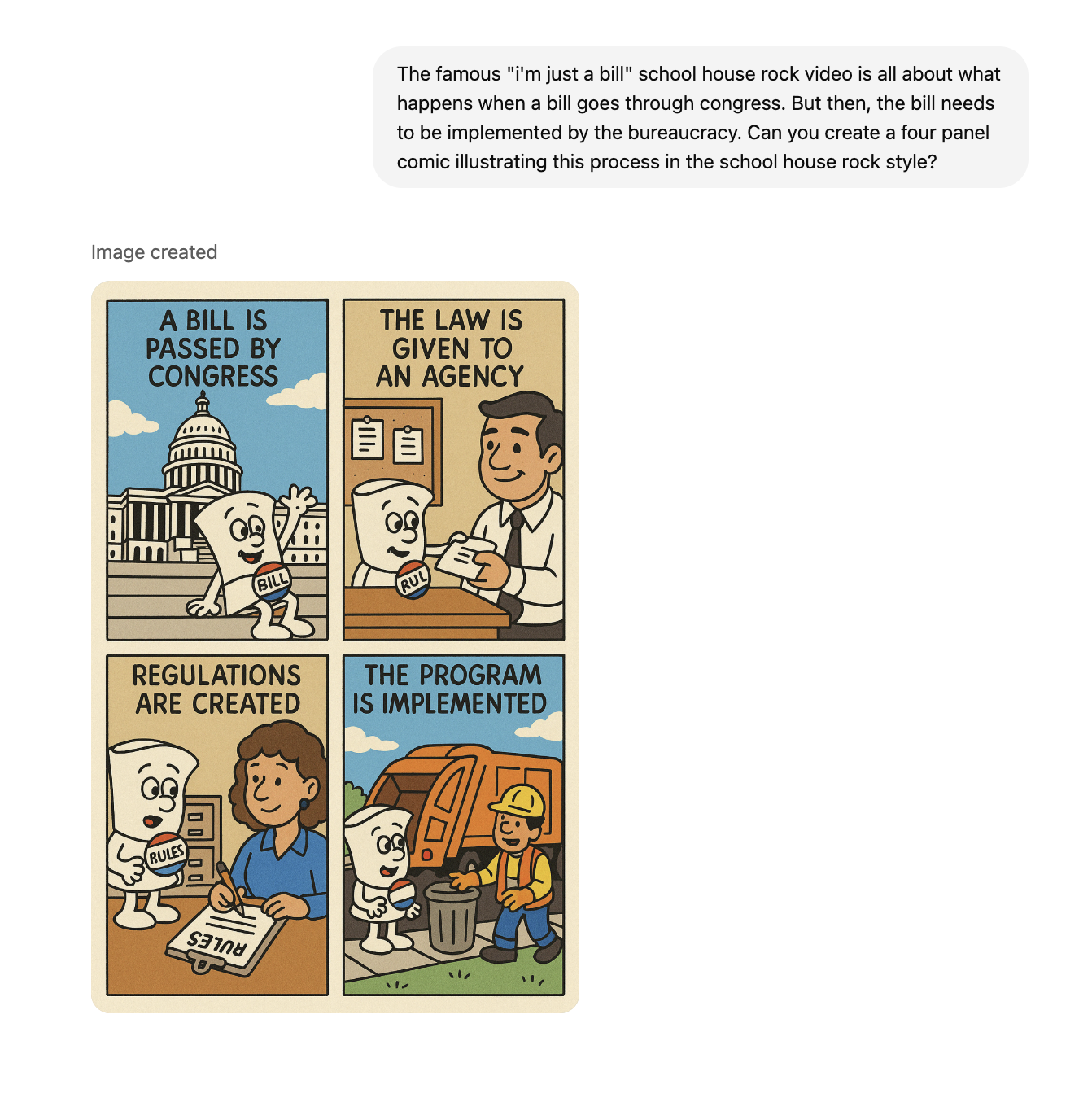

Designing Images for Slides (Obvious)

ChatGPT’s image generation tools aren’t just for turning your family photos into Miyazaki memes. I use these tools regularly to create fun and interesting images for undergraduate slides. Like this one, where I asked ChatGPT for a version of “I’m just a bill,” but for the bureaucracy.

AI image generation isn’t (in my experience) fine-tuned enough to replace a talented, human artist. But the alternative here isn’t hiring a professional designer. It’s black text on a white background. Adding AI images makes the content more memorable, keeps lecture writing fun, and occasionally elicits a chuckle from tough undergraduate audiences.

Creating Exam Questions (Ambitious)

Way back in the AI dark ages (March 2024), I was writing an open-book, multiple choice final for my undergraduate causal inference course. Then, a colleague stopped by to ask if ChatGPT could answer the questions.

As it turns out, ChatGPT got every answer right. And it provided in-depth (and factually accurate) explanations about why the correct answer was correct and why the wrong answers were wrong.

I closed the Word document and decided to come up with a new plan.

The new exam would no longer be multiple choice. It would no longer focus on factual information. Instead, students would need to analyze data, set up RDD and IV equations, and interpret the results. AI could also hack this exam, but doing so was challenging, and I was more confident in my ability to detect AI copy-paste if students had to provide written responses.

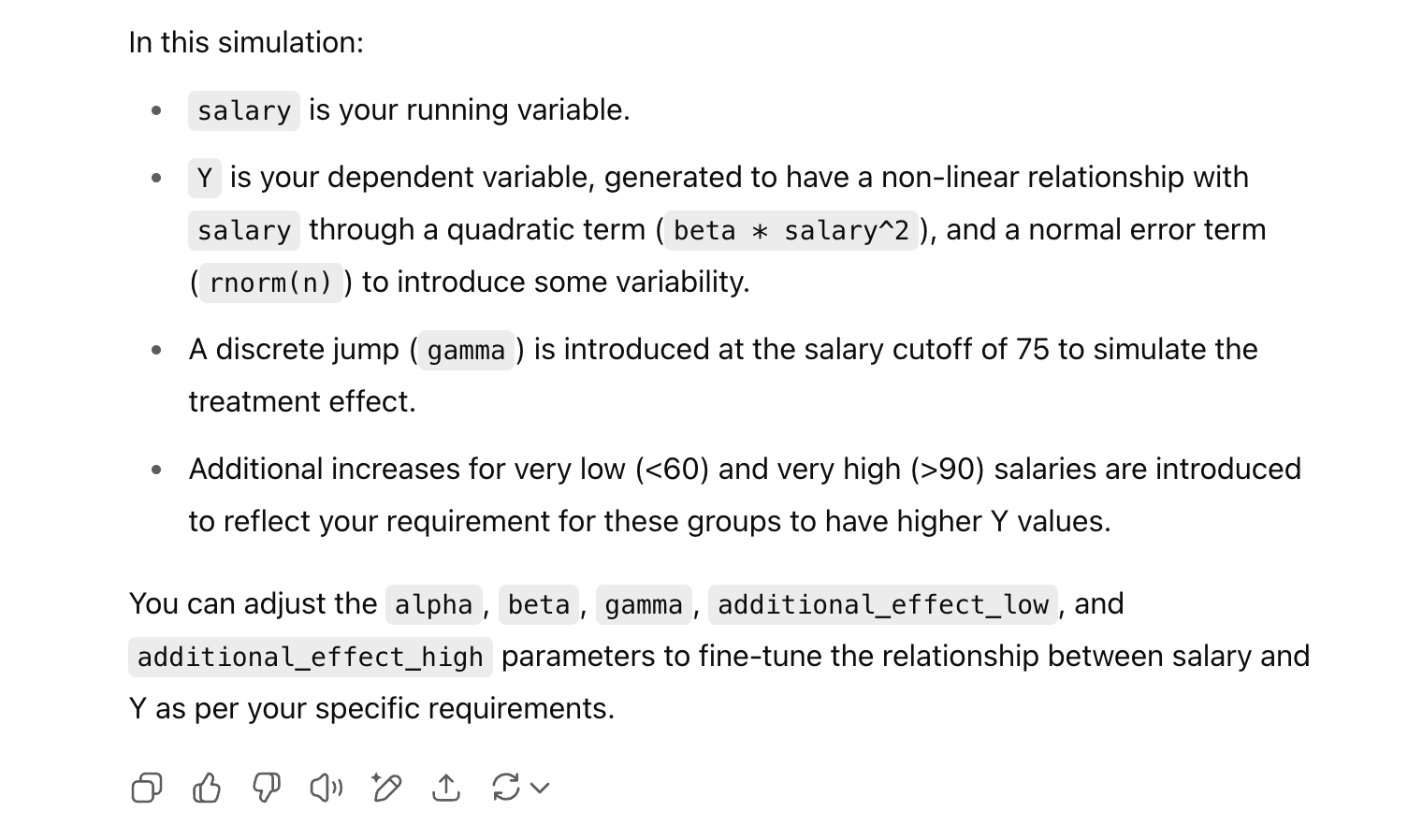

The new problem was finding suitable data. Replication datasets were too large, had too many variables, and often required modifications to conform to a classic causal design.

Simulation was the obvious answer. But I was running out of time. Fortunately, ChatGPT excels at creating data with specific properties. I described what I wanted in a single paragraph, and moments later, I had the R code I needed. That freed me to focus on where I actually add value: designing thoughtful questions that test students’ understanding.

Writing a Custom Textbook (Advanced)

No textbook is perfectly aligned with my teaching goals.

But how could one be? That’s asking too much. Or is it?

That’s the question I asked myself last quarter. And the answer is that, in the age of AI, writing a custom textbook is not only possible, it’s almost practical.

When I started teaching Intro to American Politics in the fall of 2023, I wrote detailed lecture notes to accompany my slides. Each time I taught the course, I updated slides. Added content. Changed the focus. And I kept revising my notes. But these were for personal use. They were rough, sloppy, and unprofessional.

If I could polish these notes and give them to students, I’d solve my textbook problem. But doing so seemed daunting and time-consuming.

Enter Claude.

Over a weekend, I developed a custom prompt to transform lecture notes into polished, readable textbook-style chapters for an undergraduate audience. Then, I gave the LLM my notes and asked it to go to work.

Importantly, I didn’t ask for content creation—I had already written everything using my own knowledge and insight. Claude was simply my translator.

I then carefully reviewed the output for hallucinations or factual errors the model may have introduced (there were rarely any, by the way). I extended some of the content, added images, and inserted some jokes. This process took about two hours per chapter. Not a trivial amount of work, but far less than if I had tried to write a 60,000 word book myself! Then, I posted everything online.

The result was a custom textbook, perfectly aligned with my lecture slides.

Students loved this by the way—in my spring course evals, 89% of respondents said they preferred it to a standard textbook. If you want to check it out or consider using it for your Intro to American Politics Course, you can check it out here for free. I’d love to know what you think.

The AI didn’t create content for me. Rather, the AI took what already existed (messy lecture notes) and enabled me to create a custom, high-quality, student facing resource that I can update and use again and again.

Conclusion

Are there thoughtless uses of AI that are unnecessary? Yes. Are there lazy applications that impair our ability to think critically? Absolutely.

But that doesn’t mean all use cases fall into these two buckets. There are positive use cases for this technology—use cases that may not be obvious at first, but that are both useful and even enhance critical thinking.

In none of these examples does AI “replace” me, my knowledge, or my labor. None of these examples involve me uncritically copying and pasting AI output. In every case, I apply my own judgement, taste, and subject matter expertise to achieve outcomes that would be impractical or impossible without AI assistance.

If AI can help preserve our bandwidth for important, engaging work while helping us do that work better, the real threat to critical thinking isn’t AI—it’s refusing to critically engage with it at all.